The tragic fate of Jews during WWII remains an important source of historical research and inspiration. Relevant for an exhaustive coverage of the topic are the micro-stories of people that lived during those times and further participated at the historical events in the aftermath of the war.

Tuesday, 10 November 2020

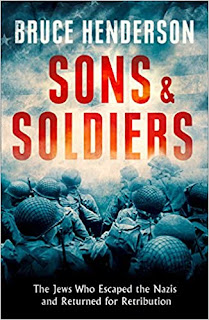

The Untold Stories of the German Jews who Returned for Retribution

Tuesday, 4 April 2017

Tutti's Promise: Jewish fate in The Netherlands

Wednesday, 4 May 2016

'They stole our childhood'...

Sunday, 7 February 2016

Jewish Life Berlin: Westhafen Memorial

Thursday, 22 September 2011

Rosh Hashanah 1944

Tuesday, 20 September 2011

Sunday, 4 September 2011

A life to tell: Vanishing traces of Jewish Galicia in present-day Ukraine

Friday, 5 November 2010

WWII mass grave of Jews found in Romania

Related articles

- Holocaust-Era Mass Grave Found in Romania (foxnews.com)

- 16 skeletons found in Romanian mass grave (cnn.com)

Monday, 14 September 2009

Survival is the Sweetest Revenge

In those years, my father, judging war films, used a Nazi-to-American kill ratio: If a lot of Nazis died, the movie was good; if those Nazis were killed by just a few Americans, the movie was potentially great.

This second criterion had everything to do with the fact that we were Jews, therefore members of a community small in number but gaudy in incident. In this way, the commandos in the Hollywood epic — I’m thinking of “The Dirty Dozen,” among others — were a stand-in for Jews as a whole. A few of us killing a lot of them — it’s a satisfying fantasy.

I’ve thought a lot about this since the release of “Inglourious Basterds,” the revenge fantasy we’ve been working toward for the last half-century. Like all masterpieces, Quentin Tarantino’s movie shows where and why other artistic expressions of this fantasy — some being very good novels and films — have failed: Simply put, they were not crazy enough, nor wild enough, nor did they go far enough.

Movies like Ed Zwick’s “Defiance,” which chronicles the exploits of Jewish partisans in occupied Poland, are crippled by their adherence to the real-life particulars of the Second World War. From the moment such a film starts, you know how the bigger story will end: The ghettos will fill and empty, the box cars will rattle down the track, the chimneys will send up plumes of black smoke. No matter how you subtract the numbers, you always wind up with the same answer: six million.

“Inglourious Basterds” succeeds as fantasy because Tarantino, who does not know better, broke every rule. (The funky spelling in the title is a warning of coming trespass.) The plot unfolds with a pleasant sense of shock — you keep expecting him to swing back and rejoin the historical narrative, but he instead keeps on, past every decency, into the black book itself, where he re-writes the most terrible moments of history, culminating in the ultimate money shot: a big, heavily armed Jew, a mountain Jew, the big Yid of yore, standing over the Führer, raking his face with machine-gun fire.

Off the charts on the Herb Cohen Nazi-to-American kill ratio, the greatest scene ever filmed, the meaning of Hollywood, why Jack Warner quit Youngstown and moved out West, though he never knew this himself.

Like all good fantasies, it works because the real world remains visible — the dream diverges, but not entirely. Simply put, there were Jews not very unlike the Jews in the movie. I wrote about a group of them in my 2000 book “The Avengers,” the story of the poet-partisan Abba Kovner, who, in the last days of the Second World War, trained a unit of Jewish partisans to kill as many Germans as possible. Plan A, which fortunately failed, was to poison the water system of a German city. Plan B was to poison the bread served daily to members of the Nazi SS being held in a prison camp awaiting prosecution for war crimes. Hundreds were hospitalized as a result, though none died.

The Inglourious Basterds are the fantasy; the Avengers were the reality. Here’s what they had in common: Both wanted to kill Nazis, both were unshaven and ragged, both were wholly unbelievable and thus often not believed in.

More interesting are the points of difference, for therein lies the answer to a great mystery: How do you continue on after the world has fallen?

For starters, Kovner did not want to hunt and kill Nazis one by one. The war had made him crazy, and in his crazed, war-ravaged mind, he believed Germans were not entitled to individualized deaths — I see you, you see me, you beg for your life, I shoot you, then you die. He believed Germans should instead be killed at random, en masse, from an emotional remove, as Germans had done to Jews.

What’s more, in its Hollywood incarnations, Jewish revenge is carried out or enabled by a righteous goy. In Tarantino’s case, this is Aldo Raine, the American lieutenant brilliantly played by Brad Pitt. But Kovner believed Jews, led by Jews and leading Jews, must take their own revenge, must carry out the retribution that God Himself, were there a God (Kovner became an atheist in the war), would have carried out. It was a point of revenge — not merely to punish the Germans but to rehabilitate the Hebrews. The Avengers would kill their way back to life, in the process leaving a marker for future generations: This is what happens if you…

“Better to die as free men fighting” — that’s how Kovner put it at the start of the war. By the end, he might as well have said: Better to kill as dead men living.

Following the war, Kovner returned slowly to life, accepting that the world had not ended and history would go on. In these months, he did something so miraculous it’s never been caught on film. He changed. He grew. He did not give up revenge so much as alter it’s meaning. He never publicly spoke of plans A and B. For him, victory would be measured not by the death of Germans but by the existence of Jews. Survival is the best answer to annihilation. As Kovner himself said, “Every Jewish town that thrives in Israel, every child that is raised, every tree that is planted — that is our revenge.”

Or, as Herb Cohen put it, “I’m here, watching a movie. Where the hell are the Nazis?”

Rich Cohen is a contributing editor at Vanity Fair and Rolling Stone. He is the author of several books, including “The Avengers: A Jewish War Story” (Knopf, 2000) and, most recently, “Israel Is Real: An Obsessive Quest to Understand the Jewish Nation and Its History” (Farrar, Straus & Giroux).

Tuesday, 11 August 2009

Monday, 3 August 2009

Saving Jewish Children, but at What Cost?

A newly disclosed directive on the this subject provides written confirmation of well-known church policy and practices at the time, particularly toward Jewish children who had been baptized, often to save them from perishing at the hands of the Nazis. Its tone is cold and impersonal, and it makes no mention of the horrors of the Holocaust.

Its disclosure has reopened a raw debate on the World War II role of the Catholic Church and of Pope Pius XII, a candidate for sainthood who has been excoriated by his critics as a heartless anti-Semite who maintained a public silence on the Nazi death camps and praised by his supporters as a savior of Jewish lives.

The one-page, typewritten directive, dated Oct. 23, 1946, was discovered in a French church archive outside Paris and made available to The New York Times on the condition that the source would not be disclosed. It is a list of instructions for French authorities on how to deal with demands from Jewish officials who want to reclaim Jewish children.

"Children who have been baptized must not be entrusted to institutions that would not be in a position to guarantee their Christian upbringing," the directive says.

It also contains an order not to allow Jewish children who had been baptized Catholic to go home to their own parents. "If the children have been turned over by their parents, and if the parents reclaim them now, providing that the children have not received baptism, they can be given back," it says.

Even Jewish orphans who had not been baptized Catholic were not to be turned over automatically to Jewish authorities. "For children who no longer have their parents, given the fact that the church has responsibility for them, it is not acceptable for them to be abandoned by the church or entrusted to any persons who have no rights over them, at least until they are in a position to choose themselves," the document says. "This, obviously, is for children who would not have been baptized."

The document, written in French and first disclosed last week by the Italian daily newspaper Corriere della Sera, is unsigned but says, "It should be noted that this decision taken by the Holy Congregation of the Holy Office has been approved by the Holy Father."

The publication of the document is likely to embolden those who do not think Pius XII is worthy of becoming a saint. Some prominent Jews and historians have attacked the document for its insensitivity to the Holocaust.

The Rev. Peter Gumpel, a Rome-based Jesuit priest and a leading proponent for the beatification of Pius XII, the first step toward sainthood, said he was convinced that the document did not come from the Vatican. He pointed out that it is not on official Vatican stationery, that it is not signed and that it is written in French, not Italian. "There is something fishy here," he said.

But Étienne Fouilloux, a French historian who is compiling Pope John XXIII's diaries during his years in France, said that the document had been discovered recently in church archives outside of Paris by a serious researcher and that it is genuine. John has been beatified, the last formal step toward sainthood.

At the time, Pope John XXIII was Monsignor Angelo Roncalli, Pope Pius XII'S representative to France. During the war, Monsignor Roncalli was credited with saving tens of thousands of Jews from Nazi persecution by using diplomatic couriers, papal representatives and nuns to issue and deliver baptismal certificates, immigration certificates and visas, many of them forged, to Jews. He also helped gain asylum for Jews in neutral countries.

"This document is indicative of a mind-set at the Vatican that dealt with problems in a legal framework without worrying that there were human beings involved," Mr. Fouilloux said. "It shows that the massacre of Jews was not seen by the Holy See as something of importance."

He said he would include the document in the next volume of the diaries.

The document underscores the sanctity with which the Vatican treated the sacrament of baptism at the time - no matter how or why it was administered.

The church's stance that a baptized child is irrevocably Christian was established nearly a century before the Holocaust, when, in 1858, papal guards took Edgardo Mortara, 6, from his family in Bologna when word spread that he had been clandestinely baptized by a Catholic maid. It was relaxed only in the 1960's.

More important, the directive captures the church's failure to grasp the enormous implications of the Nazi extermination of the Jews. "It shows the very bureaucratic and very icy attitude of the Catholic Church in these types of things." said Alberto Melloni, an Italian historian with the John XXIII Foundation for Religious Studies in Bologna, who is working with Mr. Fouilloux to publish the diaries of Pope John XXIII. He called the tone of the directive "horrifyingly normal."

A second document that was also discovered by the French researcher is a letter in July 1946 to Monsignor Roncalli that noted his pledge to intervene to return Jewish-born children to their community and asked for his help to return 30 Jewish-born children living in a Catholic charity.

"Almost two years after the liberation of France, some Israelite children are still in non-Jewish institutions that refuse to give them back to Jewish charities," said the letter, which was signed by the Grand Rabbi of France and the head of the Jewish Central Consistory. It added, "We are in advance, grateful for your help."

It is not known whether there was a reply.

No reliable figures exist on how many French Jewish children were saved by the church from the Nazis, or affected by its decision to prevent them from rejoining their families and communities after the war. The French Jewish population had limited success in recovering Jewish children who had been adopted by non-Jews.

In the most well-documented case in France, two Jewish boys, Robert and Gerald Finaly, were sent in 1944 by their parents to a Catholic nursery in Grenoble. The parents perished at Auschwitz. Family members tried to get the boys back in 1945, but in part because they had been baptized, it took an additional eight years and a long legal battle to prevail over the church.

"Look, I know that for the church, baptism means the child belongs to the church, you can't undo it," said Amos Luzzatto, the president of the Union of Italian Jewish Communities. "But given the circumstances they could have made a human decision."

Mr. Luzzatto described himself as "speechless" that the Vatican directive on the children does not mention the Holocaust and questioned the worthiness of Pius XII to be made a saint.

"If they beatify him, don't ask us to applaud," he said.

Some corners of the Catholic Church are suspicious that the document, and the ensuing debate that has played out in Italian newspapers, was produced to create obstacles in Pius XII's march toward sainthood.

But Pope John Paul II strongly supports the campaign to make Pius XII a saint, and in February 2003, the Vatican announced the opening of some secret archives to help clear Pius XII's name, although the papers do not deal with his activities as pope.

Elaine Sciolino reported from Paris for this article, and Jason Horowitz from Rome.

Sunday, 28 June 2009

From the Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp

Monday, 20 April 2009

Holocaust survivors to light torches at Yad Vashem ceremony

At this year's official Opening Ceremony for Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Day which opens Monday evening at the Warsaw Guetto Square at Jerusalem's Yad Vashem, Holocaust survivors will light six torches as short videos of their individual testimonies will be shown on screen.

The central theme selected for this year's ceremony is Children of the Holocaust, according to a Yad Vashem statement, and the survivors lighting the torches Monday evening were all young children when World War II began.

The ceremony, which will feature speeches by President Shimon Peres and Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu, memorial services by Chief Rabbis Shlomo Amar and Yonah Metzger and a 2-hour symposium entitled Through the Tears - Childhood and Youth During the Shoah - will be broadcast live on television.

These are the six survivors in the order they will appear at the traditional memorial ceremony.

Lea Paz

Lea Paz, née Weitzner, was born in 1930 in Lwow. Her father Herman, a civil judge, passed away when Lea was five, and Lea and her mother Gusta moved to the village of Kochawina to live on her grandfather's large farm.

In September 1942, Lea, Gusta and her grandmother were deported to Belzec. With rumors about the camp circulating on the train, Gusta pushed Lea out through a narrow opening in the side of the train car. Lea eventually found her way back to her grandfather and an uncle, Mundek, who had escaped the deportation. Mundek, who had lived in Mandatory Palestine but had come back to introduce his fiancée to his family and got caught in the war, was determined to save the young girl. He bought Lea false papers, and taught her Christian prayers and customs, all the while encouraging her to eventually emigrate to the Land of Israel.

Lea first lived with the Plauszewski family, and then with a relative of theirs, Stefania Gos, whose husband was a commander in the Polish underground. Her rescuers were later recognized as Righteous Among the Nations.

Just before liberation, Lea's grandfather and Mundek were turned in by one of their neighbors. After Mundek's death, the family who had hidden him, the Wohanskis (later also recognized as Righteous Among the Nations), gave Lea his two picture albums filled with photographs of Mandatory Palestine.

Lea emigrated to Palestine on an illegal immigrant ship but was arrested by the British and interned in Cyprus. During a demonstration organized by the internees in Cyprus, Lea was wounded by British police gunfire. The story was published in the Jewish press in Mandatory Palestine, thus allowing her relatives on Kibbutz Merhavia to discover that she had survived. Lea was reunited with them after she was finally allowed to immigrate into Eretz Israel. She married Ephraim, and they have two children and six grandchildren.

--------------------------------

Mirjam Schuster

Mirjam Schuster was born in 1935 in Zarojani, Moldova, to an observant Jewish family of six children. In 1941, the family was deported by Romanian soldiers and forcibly marched, together with all the Jews in the area, towards Transnistria. After more than two months of walking day and night, Mirjam and her family arrived at Balki, near the city of Bar, where thousands of Jewish prisoners were crammed into horse stables without windows or doors. The stables were terribly crowded, and rife with hunger and disease. Mirjam and her family slept on the exposed concrete floor. Her mother saw to Mirjam's needs and those of the other children, while her older sisters smuggled in food from the adjacent village.

Mirjam remembers a Jewish child named Mendele, who was smuggled into the camp by his parents. Mirjam took Mendele under her wing and protected him from other children who were bullying him. One day, the Germans found Mendele and murdered him. His horrific death left Miriam deeply scarred.

In 1944, the Soviets liberated Balki. Out of more than 10,000 inmates, only a few hundred had survived. Following liberation, the Jewish Agency placed Mirjam in a children's home. After a few months, she boarded an illegal immigrant ship, which was intercepted by the British and sent to Cyprus. Just before the establishment of the State, Mirjiam finally reached Israel's shores.

Mirjam married Moshe and has three children and eight grandchildren. After her children had grown, she began volunteering with new immigrants, helping ease their adjustment to living in Israel. Today, Mirjam is the volunteer director of the "Help for Holocaust Survivors" organization.

-----------------------------------

Solomon Feigerson

Solomon (Sjema) Feigerson was born in 1930 in Liepaja, Latvia, the middle of three sons. His older brother Hanoch was killed in June 1941, in defense of the town against the Germans. His father, Yaakov, was murdered in July 1941, and his mother and younger brother Josef were murdered at the Skede execution grounds in February 1942. Solomon escaped that and another murder operation in April by running away, despite being shot by Latvian guards.

In July 1942, the Jews of Liepaja were herded into a ghetto. Solomon lived in one room with 20 other orphaned boys. On Yom Kippur (October) 1943, the ghetto was liquidated and Solomon was deported to the Kaiserwald labor camp. There he met and bonded with Lina Goldblatt, a prisoner from Hamburg, and her daughter, Rosa. "She was like a mother to me," he recalls, "she even sewed me a shirt and a pair of pants."

In August 1944 Solomon was transferred to the Stutthof concentration camp, and in April 1945 he was put on one of four ships carrying 500 inmates, sent into the Baltic Sea to die. Solomon's ship eventually sailed into Neustadt on 3 May 1945. German sailors on the shore shot at the survivors. A British soldier found him, exhausted and ill, clutching a loaf of bread.

After the war, Solomon went to Riga. He studied engineering and started a family. While in Riga, he campaigned with Holocaust survivors and others to emigrate to Israel. He arrived in Israel in 1971 where he worked as an engineer and volunteered with a number of organizations commemorating the Holocaust and assisting survivors. He also published a book about the destruction of the Jewish community of Liepaja.

Solomon and his wife Ethel have a son and two grandchildren.

------------------------------------

Iudit Barnea and Lia Huber

Identical twin sisters Iudit Barnea and Lia Huber (nées Tchengar) were born in 1937 in the town of Şimleul Silvaniei (Szilagysomlyo), Transylvania. In 1940, Transylvania was annexed to Hungary, and in June 1942 their father Zvi was taken to a forced labor unit on the Russian front.

With the German conquest of Hungary in March 1944, the family's property and belongings were confiscated, and they were forced to wear a yellow star. In May 1944 Iudit, Lia and their mother, Miriam-Rachel, were interned in a ghetto, and the following month they were deported to Auschwitz, along with many other members of their family.

At Auschwitz, Iudit and Lia suffered the infamous medical experiments of Josef Mengele. The twins always stayed close together. Every night, their mother would sneak into their block and give them her meager portion of bread. She would also take them outside, in all weathers, to wash them and comb their hair, and thus preventing them from getting infested by lice and being doomed to the gas chambers. One day, as Mengele was experimenting on the girls, Miriam-Rachel burst into the shack and begged him to stop. In response, she was injected with a concoction that nearly killed her, and caused her permanent deafness.

In January 1945 the girls and their mother were liberated by the Red Army. They returned to Şimleul Silvaniei, and in August 1945 they were reunited with their father, who had survived many camps. In 1960 the family immigrated to Israel. Both girls married: Lia and her husband Jean have two children and seven grandchildren; Iudit and Moshe have three children and five grandchildren.

------------------------------------

Esther Debora Reiss-Mossel

Esther Debora Reiss-Mossel, the youngest child of Josef and Elsa, was born in 1938 in Heiloo, Holland to a well-known Zionist family. In 1942, her parents Josef and Elsa entrusted her to their nanny's family, but Esther refused to stay and returned home.

During the razzia (raid) of 26 May 1943 the family was sent to the Westerbork transit camp. After being hospitalized for many weeks with a number of childhood diseases, Esther went to the camp nursery, where she recalls learning Jewish and Zionist songs. On 19 January 1944 the family of five - including Esther's brother Benjamin (Ben) and sister Yetty (Yael) - was sent to Bergen-Belsen, which her father believed was a stop on the way to Eretz Israel. When her parents caught typhus, Esther was sent to an orphanage set up by Henny and Yehoshua Birnbaum. Esther remembers the eve of Passover 1945, as her father lay dying, when the Birnbaums baked matza in honor of the Festival of Freedom.

In April 1945, some 2,500 prisoners were forced onto what later became known as "the lost train." Elsa was left behind at Bergen-Belsen, where she died. For weeks, the train traveled back and forth in an attempt to reach Theresienstadt, caught in the crossfire between German and Red Army forces. Close to one quarter of the passengers died during the journey. Early in the morning of 23 April they heard a Russian soldier shout, "Comrades - freedom!" The train was finally liberated next to a destroyed bridge over the Elster River near Troebitz, some 20 km. from Leipzig. In Troebitz, Tzadok and Chana Mossel adopted Josef's children, and the enlarged family returned to Amsterdam in August. In the summer of 1950 Esther's parents' dream was realized when she immigrated with Chana and Tzadok to Israel. Today, Esther is active in commemorating Jews who saved others during the war, as well as saving the forests and hills of Judea.

Esther was married to the late architect Elimelech Reiss, who helped plan Yad Vashem's Children's Memorial. She has three daughters and five grandchildren.

--------------------------------------------

Shimon Greenhouse

Shimon (Sjema) Greenhouse was born in 1932 in Krasna, Belarus, to a traditional Jewish Zionist family. His older siblings, Henya and Mendel, were active in Zionist federations and planned to emigrate to Mandatory Palestine.

At the end of 1941, after the Germans invaded the USSR, Shimon and his family were interned in the Krasna ghetto. Shimon and his mother managed to sneak out of the ghetto and reach a Polish acquaintance who gave them food and convinced an SS officer not to kill them.

One day, after a German horse fell into a pit, the Germans gathered Jews in the ghetto's central square and shot them one by one. Shimon and his father, Yekutiel, stood there, their hands clasped. When Yekutiel was shot, he dragged his young son down with him. Shimon remained beneath his dead father, dazed and covered with blood, for a full day until family members pulled him out.

On Purim (March) 1943, the Germans liquidated the ghetto and murdered its residents, including Mendel and Henya. Shimon and his mother hid for five days with 20 other people. When they emerged, the ghetto was empty, and the air stank of incinerated bodies. As Shimon was recovering from typhus, his mother carried him on her back to the marshes, where the partisans were hiding. They survived the remainder of the war among the partisans, with minimal clothing and food.

After the war, Shimon and his mother returned to Krasna. In 1950, after Shimon completed his studies, they emigrated to Israel. Shimon married and had four children and three grandchildren. He served as an educator and high school principal in Petah Tikva, leaving his mark on generations of students.