I love the language of the graphic novels as suited to convene a variety of topics, including history and identity and religion. Three topics matching perfectly when it comes to Jewish identity. In the last months I´ve read a couple of graphic novels with Jewish topics that I am happy to further recommend.

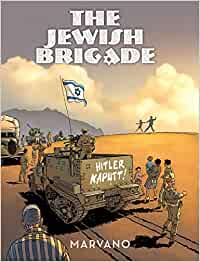

The Jewish Brigade by Marvano

This book is the second from the series created by the Belgian cartoonish Marvano. Based on true facts - Jewish soldiers hunting former Nazis in Europe at the end of the war - it recreates the ambiance of incertainty and human confusion at the end of the second World War. In few words and many inspired visual representations, there are a lot of stories told in just a couple of pages: how Jews just escaping the camps were killed by their non-Jewish neighbours, the meeting between the Russian Cold War interests and the ex-Nazis, the ways in which former Nazis escaped Europe and their punishment. Enough history and context to make you curious to find out more about it, especially if not familiar with the intricacies of those times.

Disclaimer: Book offered by the publisher in exchange for an honest review

Herzl by Camille de Toledo, illustrated by Alexander Pavlenko

Herzl written by Camille de Toledo and illustrated by Alexander Pavlenko is a story within the story, where a simple human story meets the history in the making. Ilya is a Jew who escaped the pogroms and antisemitism of Europe at a time when Herzl acknowledged the neeed for the Jews to have their own homeland. The drama of the little Ilya is the best argument in favor of such a political move. The text is elaborated and unusually rich for this genre, and the predominantly black/dark illustrations are adding the emotional dramatism to the story. I´ve read the book in the original French language.

The duo De Toledo-Pavlenko recently published a book inspired by the stories of Isaac Babel which I hope to read it soon.

Jerusalem, Ein Familienporträt by Boaz Yakin, illustrated by Nick Bertozzi

Jerusalem. A Family Portrait - I´ve read it in the German version. Ein Familienporträt - is the result of collaboration between the screenwriter and producer Boaz Yakin and illustrator Nick Bertozzi. Its focus is the story of the Halaby family - originally from Aleppo - living in Jerusalem before and during the creation of the state. The story not only dares to explore a very delicate historical period of time, but reveals so many details that one can rarely find in a ´serious´ history book, such as the story of the Communist Party in ´Palestine´.

Those three books are not only relevant from the purely Jewish history point of view, but there are also important as a way in which historical information can be treated and transmitted through literary/visual support.